In the back alleys of Shawnee, Ohio, during the late 1800s, a woman named Lizzie Lape ran one of the most successful brothels in the state-not with violence or secrecy, but with business sense that would make any modern CEO nod in respect. She didn’t hide behind false names or whispered rumors. Her name was on the door, her ledger was meticulous, and her clients came from all walks of life: farmers, railroad workers, politicians, even a few out-of-town judges. She wasn’t just a madam; she was an entrepreneur who turned vice into a structured enterprise. And while today’s online world buzzes with terms like 6 escort paris or escortgirl france, Lizzie’s operation was far more grounded, more local, and far more dangerous in its time.

She didn’t need social media to advertise. Word spread fast in small towns. A man would hear about her place from a friend who’d been there, or maybe he saw the clean curtains in the second-story windows, the lack of broken glass, the polite woman who greeted him at the door with a cup of coffee and no questions asked. Lizzie’s brothel was known for being orderly. No fights. No drunken chaos. No police raids-until they came. And when they did, she was ready.

How Lizzie Built Her Empire

Lizzie didn’t start out as a madam. She was born Elizabeth Ann Lape in 1856 in rural Ohio, the daughter of a poor farmer who died when she was twelve. By sixteen, she was working as a domestic servant in Columbus. By twenty, she was living on her own, and by twenty-three, she was running a small boarding house that quietly doubled as a place where men could find companionship. She didn’t call it a brothel. She called it a "residence for traveling gentlemen."

Her success came from three things: cleanliness, consistency, and control. She kept her women healthy by requiring regular medical checks-something almost unheard of at the time. She paid them weekly, in cash, and let them keep their earnings from private clients. She even had a small garden out back where they could grow vegetables. It wasn’t luxury, but it was dignity. And that made all the difference.

She didn’t force anyone to stay. If a woman wanted to leave, Lizzie gave her a train ticket and fifty dollars. That kind of fairness built loyalty. And loyalty meant repeat customers. Men came back because they knew what to expect. No surprises. No tricks. Just a warm room, a clean bed, and a woman who treated them like human beings, not customers.

The Legal Tightrope

Ohio had laws against prostitution, but enforcement was patchy. Rural counties didn’t care as long as it didn’t disrupt church picnics or school plays. Urban centers like Cincinnati and Cleveland cracked down harder, but Shawnee was too small, too quiet, too far off the main roads. Lizzie knew this. She paid off the local constable every month-$20 in gold, delivered in a sealed envelope. He never asked questions. He never showed up unannounced.

When state investigators finally came in 1893, it wasn’t because of complaints. It was because a rival madam in Toledo had been arrested and named names. Lizzie was implicated. The press called her "The Queen of the Back Rooms." Newspapers across the Midwest ran stories about her "bawdy empire." She was arrested, fined $500 (a fortune then), and briefly jailed. But she walked out of prison six weeks later, no worse for wear.

By then, she’d already moved her operation to a new house on the edge of town. The old building was torn down. The new one had better plumbing, more rooms, and a hidden cellar for storing supplies. She didn’t try to hide. She just adapted.

Life After the Brothel

Lizzie didn’t retire because she got tired. She retired because the world changed. The railroad brought more people through Ohio, but it also brought more scrutiny. Temperance movements grew stronger. Women’s suffrage activists began speaking out against exploitation. The 1910 Mann Act made interstate prostitution a federal crime. The rules had changed.

By 1912, she sold her property and moved to Cleveland. She opened a boarding house again, this time with no hidden rooms. She lived quietly, kept to herself, and never spoke publicly about her past. Neighbors said she was kind to children, always left cookies on the porch for the mailman. She died in 1927 at age 71. Her obituary didn’t mention prostitution. It called her "a devoted community member."

Why Her Story Matters Today

When you hear about modern sex work-whether it’s escort paris in France or digital platforms in New York-it’s easy to assume it’s all new. But Lizzie Lape proves otherwise. The same dynamics exist: demand, supply, risk, control, and survival. The tools changed. The laws changed. But the human needs? Those haven’t.

She didn’t romanticize her work. She didn’t see herself as a victim or a villain. She saw herself as someone who filled a gap. Men needed comfort. Women needed income. And she made sure both got it, safely and respectfully. That’s not just history. That’s a business model.

Modern escort services might use apps, credit cards, and encrypted messaging. But the core idea remains: a transaction between two people who want something the other can provide. Lizzie’s version was face-to-face, cash-only, and required trust. Today’s version is digital, anonymous, and often impersonal. One isn’t better than the other. They’re just different responses to the same human need.

The Forgotten Women Behind the Name

Lizzie’s story gets told, but rarely do we hear about the women who worked for her. Names like Martha, Cora, and Elsie appear in court records and tax ledgers, but their voices are gone. We know they came from poverty, abuse, or abandonment. We know they chose Lizzie because she offered safety. We know they left when they could.

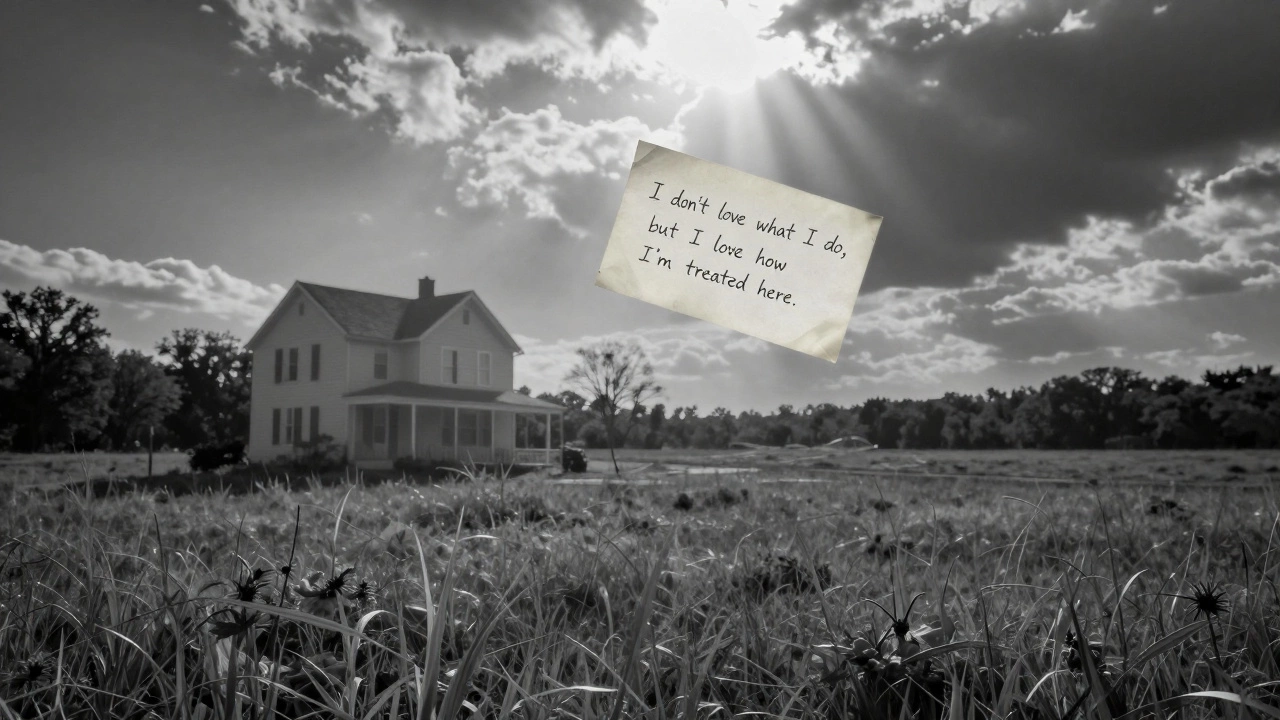

One woman, Cora, wrote a letter to a friend in 1889: "I don’t love what I do, but I love how I’m treated here. No one yells. No one hits. I get to keep my money. That’s more than most can say."

That letter was found in a sealed envelope tucked inside a Bible, buried in the floorboards of Lizzie’s old house. It was discovered during demolition in 1972. No one knows who wrote it. No one knows what happened to Cora. But her words are the clearest record we have of what Lizzie’s place really was-not a den of sin, but a refuge.

What We Lose When We Erase These Stories

History books skip over women like Lizzie Lape. They call them "fallen women," "immoral," or "criminals." But that’s not history. That’s judgment dressed up as fact. Real history is messy. It’s complicated. It’s full of people trying to survive in systems that didn’t care if they lived or died.

Lizzie didn’t change the world. But she changed the lives of dozens of women, and hundreds of men, in a quiet, steady way. She didn’t need fame. She didn’t want a monument. She just wanted to run her business without being locked up.

Today, when you hear about escort services in Paris, or in France, or anywhere else, remember: this isn’t a modern invention. It’s an old one, with roots in the same dirt, the same desperation, the same quiet dignity that Lizzie Lape understood better than anyone.

Who was Lizzie Lape and why is she significant in Ohio history?

Lizzie Lape was a madam who operated one of Ohio’s most successful and organized brothels in the late 19th century, primarily in Shawnee. She was significant because she ran her business with professionalism, prioritized the safety and payment of the women who worked for her, and avoided violent or chaotic conditions common in other establishments. Her operation lasted over two decades, survived police raids, and adapted to changing laws-making her one of the most enduring figures in the state’s hidden history of sex work.

Did Lizzie Lape ever get punished for her work?

Yes, in 1893, after a rival madam named her in court, Lizzie was arrested and fined $500 (equivalent to over $18,000 today). She spent six weeks in jail but was released without a long sentence. She avoided further legal trouble by moving her operation to a new location and continuing quietly. No further arrests are recorded after that.

How did Lizzie Lape differ from other madams of her time?

Unlike most madams who relied on fear, debt, or coercion, Lizzie treated her workers as employees, paid them weekly in cash, required health checks, and allowed them to leave whenever they chose. She maintained cleanliness, avoided public disturbances, and paid off local officials to avoid raids. Her business model was based on consistency and trust-not control or violence.

What happened to the women who worked for Lizzie Lape?

Many left when they could save enough money to start new lives-some moved to other towns, others married, a few returned to family. One worker, Cora, wrote a letter describing Lizzie’s place as a rare haven where she was treated with dignity. The letter was discovered decades later, hidden in the floorboards of the old house. Their fates are largely unknown, but their testimonies suggest they were better off under Lizzie than in most alternatives.

Why is Lizzie Lape’s story relevant today?

Her story shows that sex work has always existed, and how it’s managed makes all the difference. Modern services-whether in Paris, France, or elsewhere-still face the same issues: stigma, legality, safety, and exploitation. Lizzie’s model proves that regulation, respect, and transparency can reduce harm. Her legacy isn’t about crime-it’s about survival, agency, and the quiet power of running a business on human terms.

There’s no statue of Lizzie Lape in Ohio. No museum exhibit. No plaque on the side of the road. But if you walk through the old streets of Shawnee, past the empty lot where her house once stood, you might still feel it-the quiet echo of a woman who refused to be erased, who turned survival into strategy, and who gave dignity to those no one else would.